BACK TO TOP

CONTACT ME

|

|

Gilbert Davey was proud of his long association with the Boy's Own Paper

and its offshoot publications, and with Jack Cox. He was equally gratified

that he had introduced thousands of boys and girls to a fascinating hobby and,

in many cases, a rewarding career. (37)

All the while, he kept his life with Pearl Assurance and his writing career

quite separate. To his Company associates he was quiet, modest and unambitious;

they knew little or nothing of his spare-time radio writing career or the huge postbags

that it used to bring him. (38)

Gilbert Davey died at Peterborough on 6 April 2011, aged 97.

(1): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1957, p7.

(2): The Boy’s Own Book of Hobbies, Lutterworth Press, 1957,

article by Gilbert Davey: "The Boy’s Own Radio Den", p43.

(3): Modern Wireless, Amalgamated Press, August 1932, p130.

"Beware of Damp".

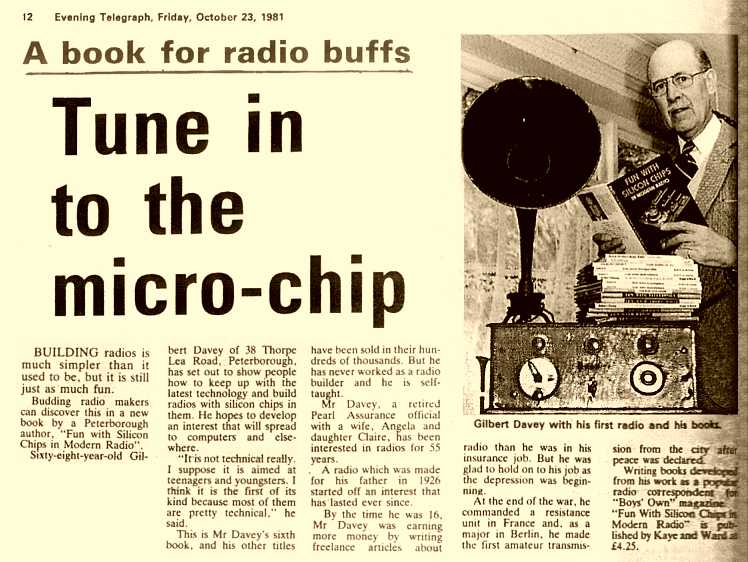

(4): Peterborough Evening Telegraph, East Midlands Newspapers Ltd, 23 October 1981,

unattributed article: "Tune in to the micro-chip".

(5): Typed list of article titles, with journals and dates, among Army records

returned to C Davey.

(6): Fun with Hi-Fi, Gilbert Davey, Kaye & Ward, 1973, pp12-13.

(7): Telephone interview with Tom Dougall (a former colleague of Davey's), 16 May 2011.

See also:

https://www.pearlstaffpensionscheme.co.uk/Members/Documents

Under "Pensions News", click the link "Pension News June 11.pdf",

then scroll to pages 14-15.

(8): Fun with Short Waves, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1960, p6.

(9): Fun with Short Waves, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1960, p10.

(10): Practical Wireless, PW Publishing Ltd,

July 2011 (p9), August 2011 (pp7-8), September 2011 (p36).

(11): The Writers' Directory 1982 - 1984, 5th edition, Macmillan Publishers Ltd, 1981, p226.

(12): Telephone interview with Tom Dougall, 16 May 2011.

(13): Fun with Short Waves, Gilbert Davey, 2nd edition, Kaye & Ward, 1968, dust-jacket flap.

(14): Boy’s Own Paper, Lutterworth Periodicals, December 1957,

unattributed article: "Hobbies for the Modern Boy", p39.

(15): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1957, p10.

(16): Email from Claire Davey, 24 November 2011.

(17): Fun with Short Waves, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1960, p6.

(18): Boy’s Own Paper, Purnell, November 1963, p22.

(19): Boy’s Own Paper, Purnell/BPC Publishing, August 1966, p48.

(20): Telephone interview with Tom Dougall, 16 May 2011.

(21): Take a Cold Tub, Sir, Jack Cox, Lutterworth Press, 1982, p119.

(22): Fun with Electronics, Gilbert Davey, 2nd edition, 1972, p48.

(23): Fun with Electronics, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, 1962, p52.

(24): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1957, pp8-9.

(25): Fun with Short Waves, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1960, p26.

(26): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 5th edition, Kaye & Ward, 1969, pp34-36.

(27): The Boy's Own Annual (1969 No 5) Purnell, pub. 1968, p39.

(28): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 5th edition, Kaye & Ward, 1969, p8.

(29): Fun with Short Waves, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, Edmund Ward, 1960, p31.

(30): Fun with Electronics, Gilbert Davey, 1st edition, 1962, p21.

(31): Fun with Hi-Fi, Gilbert Davey, Kaye & Ward, 1973, p63.

(32): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 4th edition, Edmund Ward, 1965, p44.

(33): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 4th edition, Edmund Ward, 1965, p46.

(34): Fun with Hi-Fi, Gilbert Davey, Kaye & Ward, 1973, p28.

(35): Conversation with Claire Davey, 10 September 2022.

(36): Practical Wireless, July 1990, Special Supplement (multiple un-numbered centre pages)

(37): Fun with Radio, Gilbert Davey, 6th edition, Kaye & Ward, 1978, pp9-10.

(38): Telephone interview with Tom Dougall, 16 May 2011.

|